![]()

![]()

If you enjoy this site, please check out mamster's new weblog, Roots and Grubs.

Cooking the Books

by Matthew Amster-Burton

December 11, 2000

In

the world of food writing, the last quarter of the year means two things: roast

turkey on the cover of every magazine except Vegetarian Times (Tofurkey, anyone?)

and the biggest cookbook releases from the most celebrated names in food. Roast

turkey I can do without, but I await the new cookbooks with the same lip-licking

anticipation I feel when something delicious is braising in the oven. Of course,

many of the new books are glossy, chef-oriented affairs. Two Charlie Trotter-related

books are out this year, bringing his grand total to nine books. We get it,

okay? He puts food in stacks! (At Sur La Table, the kitchen store where I work,

we sell Trotter's "Thai Barbecue Sauce," which contains balsamic vinegar.)

In

the world of food writing, the last quarter of the year means two things: roast

turkey on the cover of every magazine except Vegetarian Times (Tofurkey, anyone?)

and the biggest cookbook releases from the most celebrated names in food. Roast

turkey I can do without, but I await the new cookbooks with the same lip-licking

anticipation I feel when something delicious is braising in the oven. Of course,

many of the new books are glossy, chef-oriented affairs. Two Charlie Trotter-related

books are out this year, bringing his grand total to nine books. We get it,

okay? He puts food in stacks! (At Sur La Table, the kitchen store where I work,

we sell Trotter's "Thai Barbecue Sauce," which contains balsamic vinegar.)

Just as many, though, are potential classics. Last year gave us The Campagna Table and The Chinese Kitchen, my copies of which have become stained with olive oil and soy sauce, respectively. And though there isn't a single standout this year like 1999's The Italian Country Table, overall, this year's crop is even better.

Before I get to the books themselves, a few words on what makes a cookbook great. Having hundreds of recipes doesn't impress me; it just makes me wonder whether each was adequately thought out and tested. My favorite cookbook of all time is Cucina Simpatica (1991), by the owners of Al Forno, the unusual and rustic Italian restaurant in Providence. It runs to barely 200 pages and 125 recipes, most of which are variations on a few simple themes and all of which are perfectly suited for home cooks. John Thorne's book, reviewed here, has fewer recipes than that.

The Stranger once interviewed a member of a local band who said a great concert was one that made her want to run home and pick up her guitar. Similarly, a great cookbook is the opposite of a great novel; it's one that makes you want to throw it down and get into the kitchen as soon as possible. This can be because of great recipes, and the books below certainly have those. Recipes alone can't sustain a cookbook, though, and indeed the worst cookbooks are the glossy ones, destined for the remainder table from day one, loaded with recipes and photos but lacking voice. So one thing I look for as soon as I pick up a new cookbook is paragraphs. Great cooks are enthusiastic about food, and if that enthusiasm doesn't come through in their writing, something has gone wrong. Cucina Simpatica succeeds because:

[W]e started thumbing through old issues of Gourmet magazine. We saw in chiaroscuro a casserole of what looked like baked pasta. The lighting was dim; the background smoky and mysterious. The only clear color in the photo was a flash of red that was probably tomato. The top of the casserole looked crusty and charred as if licked by the flames of a wood-fired oven...we could almost smell the aroma from the steam curling above it.... We baked parboiled penne with fresh cream, tomato, and cheeses until the individual quills that poked out of the sauce became lightly charred. The pasta actually became impregnated with the flavor of the cheeses, and we achieved the look and spirit of the photo that had so intrigued and inspired us.

Academics have a clunky word for the felicitous union of theory and practice: praxis. I don't think I've ever been moved to use the word before, but then, few such unions are so delicious. Here are five books that achieve a similar synthesis.

Splendid

Soups

Splendid

Soups

James Peterson

640 pages, $45.00

Soup is legendarily easy to make. Start with a good broth, throw in some meat or vegetables, simmer, season, and serve. Like the legend of King Arthur, this one has some truth and a lot of myth. I've made bland soups, oily soups, monotonous soups, and cacophonous soups. I've gotten it wrong more often than right. That's why I love Splendid Soups. The book has 300 soup recipes, but it would be just as good without any.

Peterson has retained only the best aspects of his classical French training: all of the improvisation and none of the ethnocentrism. In a chapter on ethnic soups, he spends pages describing what makes a soup French, Chinese, or Moroccan, and his recommendations go well beyond a glug of veal stock or a tablespoon of hoisin sauce. In the back of the book, a chart describes the foundations of typical meat and fish soups from even more nations, including Argentina, Peru, and Belgium.

The book is divided rather loosely into broth-based, vegetable, rice, fish, shellfish, crustacean, meat, bread, dairy, and dessert soups. Plenty of the recipes could fit in a number of the categories, but the index is quite usable. Each chapter is further subdivided; for example, the broth chapter includes sections on basic broths, noodles and dumplings, eggs, and meatballs. And every chapter begins with a template for improvisation. If you want to make a mixed vegetable soup with Thai flavors, you don't even need to worry about whether there's a recipe; just turn to the Thai section at the front of the book and the beginning of the vegetable soup chapter.

The color photos were taken by Peterson himself, and perhaps because he is a cook, he has resisted the current fad of doing food photography with the minimum possible depth of field. Great! This is what your meals will look like after your failed laser eye surgery! By contrast, Peterson's shots make me want the food on a platter, not the head of the photographer. (Okay, soup on a platter wouldn't work, but anything for a severed-head joke.)

Sidebars throughout the book talk about ancillary topics like choosing fresh fish, making beurre manié, and wise use of leftovers in the soup pot. An intro chapter discusses what to drink with soup and why the choice is both simpler and more complex than it sounds. Peterson even explains which bowls and spoons he prefers and why.

One of the best things about Splendid Soups is that there is the voice of a real person behind all of this content. He is upfront about his prejudices and, better, enthusiastic about what he likes. "This soup is part of my new obsession with Indian food," he confesses while introducing a tasty-sounding curried soup of corn, coconut milk, and thyme.

See, I haven't even gotten to the recipes yet. By now I hope you've concluded, as I have, that they are icing on the cake. But what icing: French Farmer's Vegetable Soup. Spicy Brazilian Fish Soup with Coconut Milk. Senegalese Peanut Soup. Thai Hot and Sour Blue Crab Soup. Mexican Red Pepper Soup. Plus classics like Pappa al Pomodoro and consommé—real consommé, using a raft of meat to clarify the broth. (Also handy in a shipwreck.)

Authors, you are on notice. It is hard to imagine a better book on soup than this one.

Dancing

Shrimp

Dancing

Shrimp

Kasma Loha-unchit

304 pages, $30.00

There is a lot of nonsense written about Thai food, some of it certainly by me. Part of the problem is a kind of false objectivity that plagues food writing, when a writer becomes convinced that he or she has the definitive word on a topic. But plain old bullshit is a factor as well.

This became clear a couple of months ago when I took two one-night classes in Thai cooking. One was given by Su-Mei Yu, author of Cracking the Coconut. I had to take the class—she was going to be making two different kinds of phad thai. The phad thai was all right, but the instructor's pedantry was oppressive. She railed against canned coconut milk, accusing it of containing flour, which it doesn't. Then she got down on the floor to crack open a coconut and break out chunks of its flesh, which she turned over to her assistants for squeezing into milk. But the coconuts that end up in American supermarkets aren't very good, and her freshly-made coconut milk wasn't as flavorful as a quality canned brand like Chaokoh. This was only the beginning; she shrilly denounced all sorts of other shortcuts and even took a moment to go on a tirade about a person who had posted a negative review of her book on Amazon.

This is going to scare people off from cooking Thai food at home, I wrote on the class evaluation, and it's doubly the pity since Yu was so often wrong: she claimed that fish sauce is used only for flavor in Thailand and saltiness is adjusted with sea salt. But I ate numerous meals made right in front of me on the streets of Bangkok, and I never once saw someone use a pinch of salt. That doesn't mean salt is never used—I know that it's a usual ingredient in curry paste, and I'm sure it's sometimes used the way Yu said, but as a general rule? Fish sauce is the salt of Bangkok, at the very least. (Yu has posted a well-written response to many of these criticisms, which I am not the first to make.)

It was a difficult decision to publicly savage the work of a fellow food writer like this, but I decided to go ahead because Thai food is a unique pleasure and I resent the fact that Yu's puritanism is going to dissuade her readers from the satisfying experience of making it at home. In fact, because it relies less on stir-frying than Chinese food but is similarly quick-cooking, Thai food is wonderfully suited for the American kitchen, and no one conveys this delicious truth better than Kasma Loha-unchit, author of It Rains Fishes and now Dancing Shrimp.

Loha-unchit taught the other class I attended that month, and she emphasized that cooking Thai is all about tasting. Thai food balances strong flavors: the heat and fruitiness of chiles, the sourness of tamarind and lime, the saltiness of fish sauce, the sweetness of palm sugar. I like Thai food for the same reason I like punk rock: everything is turned up to eleven. Unlike in punk rock, however, it matters if the sour is much louder than the sweet.

That's why Loha-unchit asked for volunteers to come up and taste as she was preparing a salad dressing. We tasted a mixture of fish sauce, chiles, lemongrass, roasted chile paste, shallots, cilantro, and lime juice, before she had added the sugar. It was strong, tart, and delicious. Some sugar went in, and suddenly the flavors were rounder, the peppers less hot, the lime less biting, but it didn't taste sweet. We tasted no less than six times as she continued to adjust the flavor balance. Then she poured the dressing over brined and boiled shrimp. Wow.

Dancing Shrimp is all seafood recipes, but there's no reason not to use it as your general guide to Thai cooking; nearly all the recipes are amenable to substitution, and she discusses at length the special ingredients and techniques that make Thai food one of the world's greatest cuisines.

Plus, Loha-unchit has included a recipe for Fluffy Catfish Salad, which was probably the most memorable thing we ate in Bangkok. I can't wait to make it.

I have already made Pan-Fried Halibut Topped with Chilli-Tamarind Sauce, which is a wonderful way to serve any whitefish filet, and the sauce is short work in a mortar and pestle. Other recipes include Hot-and-Sour Lemongrass Tiger Prawns, Clam and Mussel Coconut Lime Soup with Oyster Mushrooms, and Salmon Poached in Green Curry Sauce with Baby Eggplants and Thai Basil. Loha-unchit made the salmon dish for our class, and it was some of the best fish I've ever had; the salmon is just barely cooked through by the heat of the sauce poured over it. Because green curry is so assertive, though, you'd probably do just as well to make the dish with a less expensive fish.

Hot

Sour Salty Sweet

Hot

Sour Salty Sweet

Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid

368 pages, $40.00

Let's get this out of the way. I am insanely jealous of the globetrotting-with-kids lifestyle of Alford and Duguid, who also wrote Flatbreads and Flavors and Seductions of Rice. This is their best book. The central question of Hot Sour Salty Sweet is: what do the cuisines of the various nations of the Mekong valley (Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Cambodia, and Yunnan province, China) have in common, and where do they diverge? Few questions could be more enjoyable to research. The authors dragged their kids and their cameras all over Southeast Asia and have returned with this book, a collection of over 200 recipes plus short essays and color photos.

It's easy to be distracted by the pictures, which are beautiful although not as food-focused as I would have liked, but the real value here is the recipes. Because the authors have spent a significant amount of time all over the continent, they've turned up truly unusual gems like a Vietnamese version of the Thai papaya salad, som tam, this one featuring starfruit and rice powder. (Rice powder is made by toasting white sticky rice in a dry skillet, then grinding it with a spice grinder or pestle. It's crunchy, smoky, and a great addition to salads and sauces.) The salad chapter is uniformly excellent, in fact; I was familiar with Thai and Laotian salads, but not the Vietnamese salad above, nor a Cambodian one of pomelo (basically a huge and non-juicy grapefruit), coconut, peanuts, and shallots. Then there's Luang Prabang Fusion Salad, a scallion and lettuce melange tossed with two different dressings, one a traditional lime-and-fish-sauce affair, the other ground pork and vinegar.

Noodle dishes are predictably strong. The best recipe I've tried so far is Chiang Mai Curry Noodles, a spicy and comforting bowl of Thai red curry and fresh Chinese egg noodles, and my boss at Sur La Table raved about Our Favorite Noodles with Greens and Gravy, perhaps better known as the Thai noodle dish rard nah. The recipe intros often include helpful travel tips so brief you might miss them. "If you order yam wun sen from a Thai menu, the only thing you know for sure is that the salad will include cellophane noodles," which we found to be quite true after ordering several yam wun sens in Bangkok.

Hot Sour works reasonably well as ethnography. The photos, recipes, and short essays don't integrate well enough, but the reader is still left with a clear image of what eating in Southeast Asia is like, and that is a large step toward understanding the cultures. Food drifts in and out of the essays as it does in life. One story begins with the children awakened by water buffalo in Laos and ends with Alford receiving a pair of high-quality pants. In between, noodles are eaten. This is my kind of story. Unfortunately, some of the essays seem to have a forced informality that can be distracting, as when Alford muses, "For dinner, well, dinner would be no problem in our family, living in Vientiane."

The question posed by Alford and Duguid at the outset is never answered explicitly; it is up to the reader to eat and think about the recipes and thereby decide what makes a dish Yunnanese, Lao, Thai, or some of each. One last compliment, couched as a complaint: the book is shaped right for the coffee table but wrong for the kitchen, which gives the impression that it's a chef-fireworks book not meant to be cooked from, and that couldn't be more false.

Asian

Ingredients

Asian

Ingredients

Bruce Cost

321 pages, $18.00

Most Asian cookbooks have a glossary of ingredients in which the author explains the three soy sauces, five-spice powder, and the like; most recommend their favorite brands. It's always a bit like pulling an American history book off the new releases shelf, though: how do I know I can trust this author's opinions on the Civil War or bean paste? What's her angle?

Wouldn't it be great, then, if there were a book by a trustworthy authority, far more comprehensive than a few pages of glossary, with pictures when necessary, and with no recipes at all except those directly inspired by discussion of the ingredients? A crash-course on shopping in Chinatown and a trusted reference tool in one? There are now two such books. One is The Asian Grocery Store Demystified (1999), by Linda Bladholm. The other is Bruce Cost's Asian Ingredients, a much-needed update of the first edition, which was published in 1989.

Cost loves to throw in quirky but undeniably useful information. I'm willing to bet the following advice about dried shiitake mushrooms has never appeared in another English-language book: "I store them in the freezer, because once in a great while, hundreds of tiny moths will hatch in one of the plastic bags, apparently from larvae that aren't included in the purchase price." Or, on a seaweed relative called hair vegetable: "At a Sichuan banquet I attended, it served as the fur of small lifelike pandas made of minced fish in a dish called Pandas at Play." He also mentions what I learned in Kasma Loha-unchit's class, that in savory dishes, palm sugar can be used to balance out sharp flavor elements like fish sauce, tamarind, and chiles.

Asian Ingredients covers not only prepackaged products but produce, meat, and fish as well. As you might guess from his enthusiasm for hair vegetable, Cost has great affection for offal and nothing but confidence that his readers would like to try some as well. The whole book is like that, a celebration of all that is delicious and simple about Asian food.

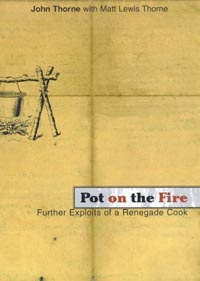

Pot

on the Fire

Pot

on the Fire

John Thorne

400 pages, $25.00

Disclaimer: Thorne is an acquaintance of mine via email and may be publishing one of my pieces in a future issue of his newsletter Simple Cooking. Does this affect my editorial judgment? Of course it does. In my defense, I liked Thorne's three previous books, which I read well before he and I ever spoke.

I've been picking on Charlie Trotter, I know, but John Thorne can be most quickly summed up as the anti-Trotter. His books have no photos and few recipes, and his stacks rise no higher than olives on bruschetta. A typical chapter will take a single dish, such as Vietnamese sandwiches or risotto, and explore it in depth you didn't know it had. Thorne is like essayist John McPhee in his conviction that the stories behind things matter, and the stories behind simple things often matter more. He is also fiercely opinionated and, where most chefs claim to like any food prepared well, upfront about his prejudices (he loves asparagus and dislikes tomato sauce).

It is the not-so-secret wish of most food writers to discover a dish that their readers have never heard of, but will be moved to make again and again. Thorne somehow does this consistently. In Pot on the Fire it's riso in bianco, short-grain Italian rice prepared like pasta: you boil the rice in salted water for 15-20 minutes, drain, and serve with a simple sauce. I tried it the same day, serving Laurie a lunch of carnaroli rice with butter, pecorino romano, and broccoli. It was as good as it sounds, and so much lighter and simpler than risotto (which is not in any way to knock risotto, another chapter in the book).

If it sounds like Pot on the Fire is starch-heavy, that's because it is. There are two other rice chapters, several concerning bread (how to toast it, how to top it, and the aesthetics of stale bread), and one long, historical essay on potatoes and the Irish. He sends emissaries to Holland in search of a cookie that charmed Roald Dahl. And just as I was going on a potsticker kick, here is Thorne with recipes for Muslim lamb filling, Korean-style goon mandu beef fillings, and shortcuts for making your own wrappers. And who else would start a chapter on pizza with Sartre and de Beauvoir famished in Naples?

Clearly Thorne knows how to pick a topic, but perhaps more important is his use of the language and his ability to talk about food anthropologically without being stilted or holier-than-thou:

Authentic pizza is, first of all, delicious crust. It is a topping that complements, even enhances, that crust. It also somehow embodies—even radiates—the craft that made it. Finally, it absorbs and momentarily resolves the tension between limited means and a desire to relax, have fun, eat something good. In the best possible situation, it is all these things. In America, pizza is most often a routinely made take-home food. Perhaps double cheese and double sausage is not meant as enhancement, after all, but rather as solace for something missing in our lives.

There in one paragraph is a cogent observation on American culture versus Neapolitan; a statement of principles on what makes pizza itself; and still it makes us want to eat pizza. Then again, everything makes me want to eat pizza.

Honorable mentions

![]()