![]()

![]()

If you enjoy this site, please check out mamster's new weblog, Roots and Grubs.

Of phad thai, prophylactics, and perpetrators

by Matthew Amster-Burton

August 26, 2000

Thanying

Thanying

10 Soi Pramuan

Th Silom

+66 2 236 4361

First, a cautionary tale.

Never tell anyone in Bangkok where you are going. On Saturday morning our waiter at breakfast casually asked us, "So, what do you have planned for today?" Chatuchak Market, we told him excitedly. We ate our free American breakfast leisurely and talked about how to get to the SkyTrain, which would drop us right in front of the market. On our way out of the hotel, however, a man appeared. "Chatuchak? I have your taxi here!" In Bangkok, you will either learn to disappoint eager touts or you will get taken for more rides than an eight-year-old at Disneyland.

You'd think that actual cab drivers would be an exception to this rule, but after trying to take a taxi to Thanying, a restaurant we'd read about in the New York Times, we were no longer so sure. We told the driver the street and name of the restaurant, and he proceeded to drop us at a completely different restaurant nearby. (Probably one run by his uncle.) This place was festooned with signboards and fountains. It looked like the Thai equivalent of a Trader Vic's. Two impresarios out front beckoned us. "You want seafood? Thai food?" For a moment it looked like we would have to give in and put our taste buds at the mercy of these hucksters. "Thanying?" I asked gamely.

In unison the dynamic duo looked at their watches, frowned, shook their heads. "Thanying?" they lamented. "Noooo...."

Of course, Thanying was actually a block away and open. The finest restaurants in Bangkok all seem to occupy former luxury houses, and Thanying's is particularly elegant.

We picked Thanying over several other possibilities because the New York Times had raved about their phad thai. We ordered some, and the waiter delivered what looked like a plain omelette. The phad thai was, in fact, inside. It wasn't bad, if a bit dry. The omelette was well cooked.

Fortunately, some of our other choices were magnificent. We had a plate of tender, lightly sauced asparagus, and an order of cashew chicken. The chicken was only mildly spiced (Thanying seemed to cater to a clientele of Western businessmen and their, um, escorts--if you are such a traveler, maybe have your companion do the ordering), but the sauce had been reduced to a perfect glaze.

Never miss an opportunity to try a Thai salad, especially if it has an intriguing name like Fluffy Catfish Salad. Chunks of catfish are fluffed with a fork, then deep fried and tossed with vegetables in a sweet and sour dressing, flavored with a hint of mango. The fish was dark and crunchy. Thailand has consistently great seafood--I am not a fish lover in general, but in Bangkok every piece of fish we had was impeccably fresh and prepared with ingenuity.

I ordered the Matsaman beef curry and found it an exemplar of its kind, with two large pieces of meat stewed to tenderness in the spicy brown gravy. I had been warned that Thai beef is tougher and gamier than high-quality American steak, but in a stew, this is an advantage--the meat was full of flavor, with good chew. I've had the dish in American restaurants and too often the already-tender beef becomes soggy.

We couldn't finish all of these dishes, but Bangkok's restaurants serve much smaller portions than their American equivalents, so it's never a problem to order three or more dishes for two people. Additionally, it is considered polite in Thai culture to leave some food on each serving plate--it makes the host look generous and the guest free of greed. Then again, it is hard to rid oneself of desire when faced with a plate of tangy fried fish.

Dinner for two with drinks and a generous tip: B1000 ($25).

Could I see a more complete menu than that, please? |

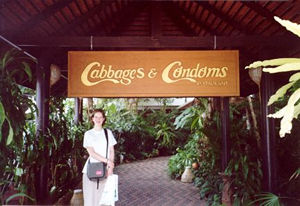

Cabbages & Condoms

10 Sukhumvit Soi 12

+66 2 229 4610

Before we left for Bangkok, we read anything and everything on Thailand we could find, including the Lonely Planet and Let's Go guides, the Traveler's Tales book, and the indispensable World Food: Thailand. From these we learned of many dishes to ask for, and how to eat with a fork and spoon. Nothing, however, warned us about some of the unusual aspects of Thai restaurant service. So consider this a Grub Shack exclusive.

1. Form an idea of what you want to eat before you sit down. Generally the menu will be presented to you and the waiter (often several waiters, as there is a labor glut) will stand there waiting to take your order. They don't mind waiting, but you will probably feel uncomfortable trying to decide between the catfish and the duck curry under the gaze of multiple servers. (Of course, the proper thing to do is order both.)

The flip side of this practice is that you are expected to pay as soon as the bill arrives. This means you have little opportunity to check the bill for errors, but if you're an American or European traveler, the price will be so low that it would be a bargain even if they charged you double. (For that matter, no one ever tried to cheat us in a restaurant.) Change is always brought promptly, so you'll never experience the post-meal limbo common in the American bill-settling process.

2. Water in restaurants is usually bottled. I believe this is done to demonstrate that their water is purified. (Thai tap water is notoriously nonpotable.) If bottled water is brought to your table, it will be free. It can be disconcerting to see the bottles piling up on your table, since in an American restaurant it's akin to watching your wallet get drained. Some restaurants do serve ice water in glasses--you don't have to worry whether this is purified. If water is not brought, request it: khaw naam plao.

Both of these practices caught us a bit off guard at the wonderful and strangely-named Cabbages & Condoms, which is run by the Thai equivalent of Planned Parenthood. All profits go to promoting contraception and AIDS prevention, and the restaurant is festooned with funny condom cartoons. Yet the space is tasteful and relaxing.

Cabbages is just a block off the Sukhumvit Road tourist ghetto, but it's like stepping into a jungle hideaway. The entrance is overgrown with vegetation, and you proceed through a teakwood entrance hall, past the gift shop, before reaching the restaurant. This must all sound kitschy, but it's not--it's delightful.

All of this would be moot if the food weren't good, but it's brilliant. The menu is extensive, and nothing we ordered was less than delicious. (I am working hard here to avoid using the word "orgasmic," tempting as it is.) Cabbages has several other branches throughout Thailand and this year they opened one in Sydney with some sort of Olympics tie-in. If they opened one in the U.S., it would be a smash hit, to the consternation of Moral Majoritarians everywhere.

Our meal began with beggar's purses, little dumplings of shrimp and chicken tied with a string of green onion and quickly deep fried. These were the best Chinese-style dumplings I've ever had: simple, attractive, not at all oily, and a perfect expression of their ingredients. Laurie and I continued to swoon over these for the rest of the trip, and the mere mention of Beggar's Purses is enough to make us check the latest Bangkok ticket prices.

And that was just the appetizer. For our main course, we ordered yam woon sen, a cellophane noodle salad stir-fried with chunks of shrimp, chicken, and red onion; a simple stir-fry of chicken and mixed vegetables; and the amazing fried cottonfish.

Every Thai fish, it seems, carries a name that trumpets its light and fluffy nature, and this is no idle boast. The cottonfish, served headless but otherwise whole, was served with a pair of dipping sauces, the usual naam pla prik and a sour mango-shallot sauce. We demolished that fish. It was crispy and light like the best fried chicken, with fresh fish flavor. And how could two sauces each be the perfect accompaniment?

Lunch for two, no drinks: B370 ($9.25)

Sara-Jane's

Sindhorn Building

130-132 Th Witthayu

+66 2 650 9992

Thai cuisine in the U.S. seems to be stuck where Italian and Chinese were decades ago: hugely popular, but with little recognition of the fact that major regional cuisines exist within the country.

So now, while there are enough Szechuan and Northern Italian restaurants to choke an ox, there isn't a single Isaan restaurant in Seattle, at least none willing to admit it. I have dreams about secret menus, and have just taught myself to say, "Do you have an Isaan menu?" in Thai. Mee rai kaan aahaan isaan mai?

Isaan is the northeastern region of Thailand. Its largest city is Khon Kaen. The Isaan are known for being especially adventurous eaters--geckos and ant larvae are popular delicacies in the region. But the core of Isaan eating is a trio of dishes which occasionally appear on the menus of American Thai restaurants but never with the authenticity or delectable variety as at a true Isaan restaurant like Sara-Jane's.

The restaurant is a cavalcade of ironies. The owner, Sara-Jane Angsuvarnsiri, is from Boston. Sara-Jane's is billed as Isaan and Italian food. Sara-Jane herself is neither Isaan nor Italian--Angsuvarnsiri is her married name. The restaurant is in an office tower on the diplomatic strip of Thanon Witthayu. It looks like an American corporate dining room.

And yet Sara-Jane's was the least Western eating experience we had in a Bangkok restaurant. The servers spoke no English at all. All the other patrons were Thai. The spiciness of the food was untamed.

The three basic Isaan dishes are som tam, gai yang, and laap. Som tam, a green papaya salad, is covered in my street food report. It's the quintessential street food, so we didn't order any at Sara-Jane's.

Gai yang simply means grilled chicken, but that's like saying southern barbecue is merely grilled pork. The comparison is apt: the chicken is marinated and then slow-cooked on a grill, leaving the skin crisp and tangy and the flesh juicy. The marinade in this case, though, contains lemongrass, garlic, coriander root, and fish sauce.

Gai yang is always served with various naam jim, dippping sauces. At Sara-Jane's we got a sweet-and-sour sauce, naam pla prik, and a more intense naam pla prik thickened with rice powder.

|

THAT SMELL Siam on Broadway serves a chicken laap. A friend of ours ordered it recently at dinner. "This is good," he said, "but it's stinky." Raw fish sauce is like that. Maybe this is why Isaan food hasn't taken over the world.

|

Rice powder is another technique that sets Isaan food apart. Borrowed from Laos, it is made by dry-toasting white sticky rice and then grinding it coarsely in a spice grinder or with a mortar and pestle. You can make it at home with a coffee grinder.

This secret ingredient is what gives laap its crunch. Laap (also spelled larb, laab, and even lard) is chopped meat salad, and Sara-Jane's offered about a dozen different varieties.

We decided on one laap with beef (laap neua) and one with chicken and cellophane noodles (laap woon sen). Both were hot and sour, crunchy and chewy. Like satay (see street food), laap and Isaan food in general are served with sticky rice. In a restaurant, the rice stays warm in a lidded basket shaped like a tin can.

For dessert, we had sticky rice with mango and coconut milk, a dish that only works when the mango is fresh. Luckily, in Thailand the mango is always fresh (I think this is the new tourist bureau slogan), so the dessert was great.

We also tried the New York cheesecake. The restaurant may be Sara-Jane's, but the cheesecake was Sara Lee.

Dinner for two with large Singha: B350 ($8.75)![]()

![]()